GUIDE TO INFECTION CONTROL IN THE HEALTHCARE SETTING

ISOLATION OF COMMUNICABLE DISEASES

Authors: Eric Nulens, MD, PhD

Chapter Editor: Gonzalo Bearman MD, MPH, FACP, FSHEA, FIDSA

Print PDF

KEY ISSUES

The combination of standard precautions and isolation procedures represents an effective strategy in the fight against healthcare associated transmission of infectious agents. Current CDC-HICPAC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee) proposed guidelines1, describing the methods and indications for these precautions are straightforward, but effective barriers at the bedside are sometimes still lacking today. Key factors in achieving effective containment of healthcare associated transmission in all hospitals are the availability of the necessary financial and logistic resources as well as the increase in compliance of healthcare professionals (HCPs) with these guidelines. Preventing transmission of infections by means of isolation procedures in a scientific and cost-effective manner represents a challenge to every healthcare institution. In 2007, the indications and methods for isolation as described in 19962were updated taking into account the changing patterns in healthcare delivery, emerging pathogens and most importantly, additions to the recommendations for standard precautions. Moreover, the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant, healthcare associated, pathogens necessitated specific strategic approaches3, which cannot be considered separately from other isolation policies.

KNOWN FACTS

- Isolation and barrier precautions aim to reduce or eliminate direct or indirect patient-to-patient transmission of healthcare associated infections that can occur through three mechanisms:

- Via contact, which involves skin (or mucosa) to skin contact and the direct physical transfer of microorganisms from one patient to another or via hands of an HCP, and indirect via a contaminated surface.

- Via respiratory droplets larger than 5 μm, which are not suspended for long in the air and usually travel a distance of less than 1 meter.

- Airborne transmission: particles 5 μm or smaller remain suspended in the air for prolonged periods, and therefore can travel longer distances and infect susceptible hosts several meters away from the source.

- Besides patient-to-patient transmission, healthcare associated infections can be endogenous (patient is the source of pathogen causing the infection) or acquired (exogenous) from environmental sources like contaminated water supplies, medical equipment, IV solutions, etc. These infections are not prevented by isolation precautions.

- The most cost-effective, simple, and feasible way to prevent transmission of pathogens, consists in a two-tier approach as described in the CDC-HICPAC guidelines1:

- Standard precautions represent a basic list of hygiene precautions designed to reduce the risk of healthcare-associated transmission of infectious agents. These precautions are applied to every patient in a healthcare setting.

- In addition to standard precautions, extra barrier or isolation precautions are necessary during the care of patients suspected or known for colonization, or an infection with highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens. These practices are designed to contain airborne-, droplet-, and direct or indirect contact transmission.

- Isolation and barrier precautions have also proven successful in limiting the epidemic spread of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA), and vancomycin resistant enterococci4(VRE). Isolation precautions are also assumed effective in other healthcare-associated transmissions caused by vancomycin intermediate or resistant Staphylococcus aureus5(VISA, VRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae, quinolone- or carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosaand Enterobacteriaceae, and multi-drug resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Acinetobacter6

SUGGESTED PRACTICE

All patients receiving care in hospitals or doctor offices, irrespective of their diagnoses, must be treated in such a manner as to minimize the risk of transmission of any kind of microorganisms from patient to HCP, from HCP to patient, and from patient to HCP to patient.

Standard Precautions

- Standard precautions are designed to reduce the risk of transmission from both recognized and unrecognized sources of infection. Hand hygiene among HCPs constitutes the single most important prevention of nosocomially transmitted infections. These precautions combine the major features of universal precautions7and body substance isolation8, and are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions except sweat, non-intact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. HCPs should wash hands when soiled, and disinfect hands, irrespective of whether gloves were worn. Gloves should be worn if there is contact with blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or when potentially contaminated objects are manipulated. Gloves must be changed between patients and before touching clean sites on the same patient. Hand hygiene should be applied immediately after gloves are removed, before and between patient contacts. A mask and eye protection as well as a gown should be worn to protect mucous membranes, skin, and clothing during procedures that are likely to result in splashing of blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions. Patients, HCPs, or visitors must not be exposed to contaminated materials or equipment. Reusable equipment should be cleaned and sterilized before reuse and soiled linen should be transported in a (double) bag.

- HCPs must protect themselves against bloodborne contamination by carefully handling sharp instruments. Needles should not be recapped, and all used sharps instruments must be placed in designated puncture-resistant containers.

- No special precautions are needed for eating utensils and dishes since hot water and detergents in hospitals are sufficient to decontaminate these articles. Rooms, cubicles, and bedside equipment should be appropriately cleaned.

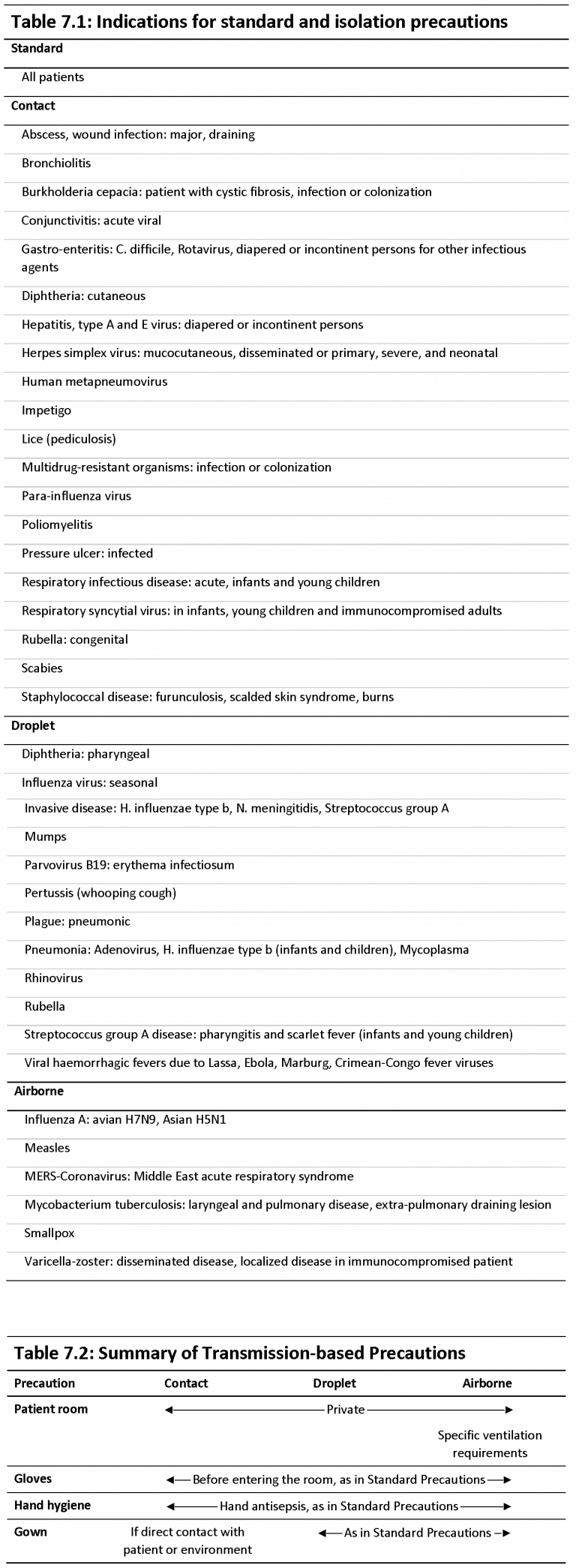

- In addition to these standard precautions, ‘transmission-based precautions’ must be used for patients known or suspected to be infected with highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens, which can spread by droplet or airborne transmission or by contact with dry skin or contaminated surfaces. Examples of conditions necessitating isolation precautions and a summary of measures to be taken are shown in Tables 7.1 and 7.2.

Tables

Contact Precautions

- Contact precautions are essential whenever transmission may occur by skin-to-skin contact and the direct physical transfer of microorganisms as shown in Table 7.1.

- Provide a private room, otherwise, cohort patients infected with the same microorganism but with no other infection. Nonsterile gloves should be worn before entering the room. Apply hand washing and hand antisepsis as in standard precautions. Do not touch potentially contaminated surfaces or equipment. Wear a clean, nonsterile gown when entering, and remove it before leaving the room. Limit transport of patients to medically necessary purposes, and maintain isolation precautions during transport. When possible, limit the use of patient-care equipment to a single patient.

Droplet Precautions

- Droplet precautions are applied for patients infected with pathogens that spread by respiratory droplets larger than 5 μm, produced during coughing, sneezing, talking, or during invasive procedures, such as bronchoscopy and intubation (see Conditions in Table 7.1).

- Provide a private room or maintain spatial separation of at least 1 m between the infected patient and other patients and visitors. Patients with excessive cough and sputum production should receive a single room first. Special ventilation is unnecessary and the door may remain open. Masks are worn within 1 meter (3 feet) of the patient.

- Limit transport of patients to medically necessary purposes, and maintain isolation precautions during transport. When possible, limit the use of patient-care equipment to a single patient.

Airborne Precautions

- Airborne precautions are applied for patients infected with pathogens spread by respiratory droplets 5 μm and smaller, produced during coughing, sneezing, talking, or during invasive procedures, such as bronchoscopy (see Conditions in Table 7.1). Therefore, susceptible healthcare personnel are restricted from entering the rooms of patients known or suspected to have measles, varicella, disseminated zoster, or smallpox. As for the other infections requiring airborne precautions, patients with suspected or known infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosisshould be nursed in a private room where the air flows in the direction from the hall into the room (negative air pressure), with 6 to 12 (optimal) air changes per hour, and appropriate discharge of air outdoors.

- High-efficiency filtration is necessary if the air is circulated in other areas of the hospital. Keep the door closed. Cohorting can be done in rare circumstances for patients infected with strains presenting with an identical antimicrobial susceptibility.

- Respiratory protection must be worn both by HCPs and visitors when entering the room. The technical requirements for respiratory protection devices remain controversial: CDC guidelines9advocate masks with face-seal leakage of 10% or less and filter 1 μm particles for 95% efficiency or higher (N95). However, a moulded surgical mask may be as effective in dealing with healthcare associated outbreaks and better complied with because of cost. Patient transport through other areas of the facility should be avoided. However, if transport is unavoidable, the patient should wear a surgical mask that covers both mouth and nose.

- Isolation is maintained until the diagnosis of tuberculosis is ruled out or, the patient is on effective therapy, improving clinically and has three consecutive sputum smears excluding the presence of acid fast bacilli. Patients infected with multidrug-resistant tuberculosisshould stay in airborne isolation throughout the hospitalization.

- For certain (syndromic) infections a combination of isolation precautions is applied until certain infectious agents are ruled out1. HCPs should additional wear personal protective equipment (PPE) that fully cover eyes, skin, and mucosal membranes when patients with presumptive infections like Ebola virus, MERS coronavirus12, and novel influenza A viruses, avian influenza A(H7N9), Asian(H5N1)13, are admitted in a healthcare facility. Aerosol generating procedures should be limited or else performed in the room or more ideally in an airborne infection isolation room if feasible11.

Protective Environment

- A set of prevention measures termed ‘Protective Environment’ has been described in the CDC-HICPAC guidelines comprising engineering and design interventions that decrease the risk of exposure to environmental fungi and other infectious diseases, for severely immunocompromised allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients during their highest risk phase.10

- Specific air quality requirements include:

- HEPA filtration of incoming air;

- directed room air flow;

- positive room air pressure;

- well-sealed rooms;

- ventilation to provide 12 air changes or more per hour;

- strategies to minimize dust;

- routinely cleaning crevices and sprinkler heads; and

- prohibiting dried and fresh flowers and potted plants in the rooms

- Protective environment does not include the use of barrier precautions beyond those indicated for standard and transmission-based precautions.

Implementation of Isolation Precautions

- A major challenge to avoid transmission of microorganisms is to raise awareness of hospital-acquired infections and to change the mindset of HCPs and hospital management. Hospitals are encouraged to review the recommendations and to modify them according to what is feasible and achievable.

- The success of transmission prevention in each institution relies on three keystones:

- An unambiguously written document describing the indications and procedures for isolation, available to all HCPs.

- Successful implementation of the procedures through clear objectives and education of all HCPs.

- Monitoring of the compliance with isolation procedures in a continuous improvement program.

- Since clear indications and advised practices for isolation procedures are available to date, the further success of transmission prevention further relies upon:

- Accurate and early identification of patients at risk requiring isolation by:

- unambiguously described criteria for starting and discontinuing isolation;

- Initiation of isolation procedure as soon as the infectious disease is suspected;

- Active surveillance of risk factors among patients upon admission to the hospital or ward; and

- Early laboratory diagnosis.

- Effective discharge planning for patients in isolation to be transferred to other healthcare facilities and effective admission planning for patients at risk of carrying infectious agents from other hospitals or nursing homes.

- Increased compliance of patients with the precautions through supportive efforts to facilitate adherence and through education about the mechanism of transmission and the reason for being placed in isolation.

- Instruction and information of visitors about infection prevention measures.

- Clear endorsement by hospital management and department heads.

SUGGESTED PRACTICE IN UNDER-RESOURCED SETTINGS

- The recommendations described in the guidelines published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, and The International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium, should be feasibly applicable to infection control programs in settings with limited resources. However, there is a significant gap between the contents of the available recommendations and the feasibility of their implementation at hospitals, due to the actual structure, supplies, technology, knowledge, skills, and practices. Furthermore, their effectiveness is hindered by the existence of unfavorable situations, including overcrowded intensive care units, insufficient rooms for isolation, lack of sinks, and lack of medical supplies. Limited supplies and adopting unsafe practices, serve as an obstacle to applying maximal barrier precautions. In order to reduce the hospitalized patients’ risk of infection, a multidimensional approach is primary and essential.

- The International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium was founded in 1998 to promote evidence-based infection control in limited-resource countries through the analysis of surveillance data collected by their affiliated hospitals. The International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium is an international, nonprofit, multi-centric healthcare-associated infection cohort surveillance network with a methodology based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network.

Reference: Rosenthal VD, International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) resources: INICC multidimensional approach and INICC surveillance online system. Am J Infect Control.2016; 44(6): e81-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.01.005; abstract available at http://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(16)00043-2/abstract

SUMMARY

Every patient is potentially at risk for acquiring and transmitting infectious diseases to other patients and healthcare workers. Therefore, standard precautions should be applied for patients admitted in a hospital. In addition to standard precautions, extra barrier or isolation precautions are necessary during the care of patients suspected or known for colonization or an infection with highly transmissible or epidemiologically important pathogens. These practices are designed to contain airborne-, droplet-, and direct or indirect contact transmission. Furthermore, these precautions also may contain the transmission of multiple-drug resistant organisms. Some severely immunocompromised patients are nursed in protective isolation to decrease the risk of exposure to infectious diseases. The success of transmission prevention in each institution relies on several keystones: written documents describing isolation procedures, successful implementation of the procedures, monitoring of the compliance with isolation procedures, and the collaboration between the different hospital departments during the stay and investigations of the patient.

REFERENCES

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings; available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docket/archive/pdfs/NIOSH-219/0219-010107-siegel.pdf

- Garner JS. Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996; 17(1):53-80; extract available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/30142367

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Management of Multidrug-Resistant Organisms in Healthcare Settings. 2006; available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/MDRO/MDROGuideline2006.pdf

- Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Recommendations for Preventing the Spread of Vancomycin Resistance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995. 16(2):105-13; extract available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/30140952

- Edmond MB, Wenzel RP, Pasculle AW. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Perspectives on Measures Needed for Control. Ann Intern Med. 1996. 124(3):329-34; abstract available at http://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/709426

- Flaherty JP, Weinstein RA. Nosocomial Infection Caused by Antibiotic-Resistant Organisms in the Intensive Care Unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996. 17(4):236-48; extract available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/30141027

- Perspectives in Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Update: Universal Precautions for Prevention of Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B Virus, and Other Bloodborne Pathogens in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988; 37(24):377-88, 387-8; available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00000039.htm

- Lynch P, Cummings MJ, Roberts PL, et al. Implementing and Evaluating a System of Generic Infection Precautions: Body Substance Isolation. Am J Infect Control. 1990. 18(1):1-12; abstract available at http://www.ajicjournal.org/article/0196-6553(90)90204-6/pdf

- Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosisin Health-Care Settings, 2005. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005. 54(RR17): 1-141; available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5417a1.htm

- Guidelines for Preventing Opportunistic Infections Among Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Recommendations of CDC, the Infectious Disease Society of America, and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000. 49(RR-10):1-128; available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4910a1.htm

- Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Hospitalized Patients Under Investigation (PUIs) for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in U.S. Hospitals. 2014; available at https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/hospitals/infection-control.html

- Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Hospitalized Patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), 2017; available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/infection-prevention-control.html

- Interim Guidance for Infection Control Within Healthcare Settings When Caring for Confirmed Cases, Probable Cases, and Cases Under Investigation for Infection with Novel Influenza A Viruses Associated with Severe Disease, 2016; available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/novel-flu-infection-control.htm